Oso noizean behin ingelesezko sarrera bat jarri behar dugu blog honetan. Zergatiak? Alde batetik erabilitako ingelesa erraza delako, plain English edo. Bestetik, gaia oso garrantzitsua delako, zorra; eta eztabaida funtsezko delako, eta badaezpada ere, zehaztasunak ez galtzeko edo. Gainera, kasu honetan Nobel saridun bat, P. Krugman, dugu alde batean eta W. Molser bestean.

Krugman kolore beltzez.

Mosler kolore urdinez.

(Euskarazko egokitzapena kolore moreaz.)

(Gozatu eta ikas!)

Krugman on debt

http://moslereconomics.com/2015/08/22/krugman-on-debt/

Debt Is Good

By Paul Krugman

Aug 21 (NYT) — Rand Paul said something funny the other day. No, really — although of course it wasn’t intentional. On his Twitter account he decried the irresponsibility of American fiscal policy, declaring, “The last time the United States was debt free was 1835.”

Which consequently was followed by the worst depression in US history.

(Eta jarraian AEBko historian depresiorik txarrena egon zen.)

Wags quickly noted that the U.S. economy has, on the whole, done pretty well these past 180 years, suggesting that having the government owe the private sector money might not be all that bad a thing. The British government, by the way, has been in debt for more than three centuries, an era spanning the Industrial Revolution, victory over Napoleon, and more.

But is the point simply that public debt isn’t as bad as legend has it? Or can government debt actually be a good thing?

Believe it or not, many economists argue that the economy needs a sufficient amount of debt out there to function well.

Yes, to offset desires to not spend income (save) when private sector borrowing to spend isn’t sufficient, as evidenced by unemployment.

(Bai, desioak konpentsatzeko errenta ez gastatzearren (aurreztu) sektore pribatuaren maileguz hartzea gastatzeko nahikoa ez denean, eta horren froga langabezia izanik.)

And how much is sufficient? Maybe more than we currently have. That is, there’s a reasonable argument to be made that part of what ails the world economy right now is that governments aren’t deep enough in debt.

Yes, it’s called unemployment, which is the evidence that deficit spending is insufficient to offset desires to not spend income. Something economists have known by identity for at least 300 years

(Bai, langabezia deitzen da, eta horren froga defizit gastua ez dela nahikoa desioak konpentsatzeko, errenta ez gastatzearren. Zerbait ekonomialariek identitate gisa ezagutu dutena gutxienez 300 urtetan.)

I know that may sound crazy. After all, we’ve spent much of the past five or six years in a state of fiscal panic, with all the Very Serious People declaring that we must slash deficits and reduce debt now now now or we’ll turn into Greece, Greece I tell you.

But the power of the deficit scolds was always a triumph of ideology over evidence, and a growing number of genuinely serious people — most recently Narayana Kocherlakota, the departing president of the Minneapolis Fed — are making the case that we need more, not less, government debt.

Why?

This is the right answer- because the US public debt, for example, is nothing more than the dollars spent by the govt that haven’t yet been used to pay taxes. Those dollars constitute the net financial dollar assets of the global economy (net nominal savings), as actual cash, or dollar balances in bank accounts at the Federal Reserve Bank called reserve accounts and securities accounts. Functionally, it is not wrong to call these dollars the ‘monetary base’. And a growing economy that generates increasing quantities of unspent income likewise needs an increasing quantity of spending that exceeds income- private or public- for a growing output to get sold.

(Hau da erantzun zuzena – zeren eta AEBko zor publikoa, kasurako, gobernuak gastatutako eta oraindik zergak ordaintzeko erabili izan ez diren dolarrak besterik ez baitira. Dolar horiek ekonomia globalaren finantza aktibo netoak (aurrezki nominal netoak) osatzen dituzte, benetako esku-diru gisa, edo Erreserba Federaleko banku-kontuetan eta titulu kontuetan dolar balantze moduan. Funtzionalki, ez dago gaizki dolar horiek ‘oinarri monetarioa’ deitzea. Eta gero eta handiago den ekonomia batek, gero eta handiagoko ez gastatutako errenta-kopurua sortzen duenak era berean errenta -pribatua edo publikoa- gainditzen duen gero eta gastu handiagoa behar du, handituz doan outputa saldu ahal izateko.)

One answer is that issuing debt is a way to pay for useful things, and we should do more of that when the price is right.

Wrong answer. It’s never about ‘when the price is right’. It is always a political question regarding resource allocation between the public sector and private sector

(Erantzun okerra. Ez da inoiz ‘prezioa noiz den zuzen’ari buruz. Sektore publikoaren eta sektore pribatuaren arteko baliabideen esleitzeari buruzko kontu politikoa da beti.)

The United States suffers from obvious deficiencies in roads, rails, water systems and more; meanwhile, the federal government can borrow at historically low interest rates.

Wrong answer. Yes, there is a serious infrastructure deficiency. The right question, however, is whether the US has the available resources and whether it wants to allocate them for that purpose.

(Erantzun okerra. Bai, badago azpiegituraren gabezia larria. Galdera zuzena, ordea, hauxe da: AEBk baliabideak ote dituen eta horiek helburu horretarako esleitu nahi dituen ala ez.)

So this is a very good time to be borrowing and investing in the future, and a very bad time for what has actually happened: an unprecedented decline in public construction spending adjusted for population growth and inflation.

I agree it’s a good time to fund infrastructure investment, due to said deficiencies.

However, whether or not it’s a good time to increase deficit spending is a function of how much slack is in the economy, as evidenced by the unemployment rates, participation rates, etc. And not by infrastructure needs.

And my read based on that criteria is that it’s a good time for proactive fiscal expansion.

Nor in any case is deciding whether or not to increase deficit spending rightly about whether or not to increase borrowing per se for a government that, under close examination, from inception necessarily spends or lends first, and then borrows. As Fed insiders say, ‘you can’t do a reserve drain without first doing a reserve add.’

(Ados nago, une egokia da azpiegituraren inbertsio finantzatzeko, aipatutako gabeziak direla eta.

Hala ere, defizit gastua handitzeko momentu egokia den ala ez, ekonomiaren zenbat moteltasun dagoenaren funtzioa da, eta horren froga gisa langabezia tasak, parte-hartze tasak eta abar dira. Eta ez azpiegituraren beharrak.

Irizpide horretan oinarrituta, nire irakurketa da tenore ona dela aurreranzko hedapen fiskalerako.

Inongo kasutan afera ez da defizit gastua handitzea ala ez behar bezala mailegatzea handitzea ala ez per se, gobernu baterako, zeina, azterketa estuaren azpian, hasieratik nahitaez lehendabizi gastatu edo maileguz ematen duen eta gero maileguz hartu. Fed-ekoek diotenez, “ezin duzu erreserba drainatze bat egin lehenago erreserba gehigarri bat egin gabe.”)

Beyond that, those very low interest rates are telling us something about what markets want.

Wrong, they are telling is something about what level market participants think the fed will target the Fed funds rate over time.

(Oker, esaten dutena da merkatu parte-hartzaileek pentsatzen dutenari buruz, hots, Fed-ek Fed-eko fondoen tasa, denboran zehar, zein helburu maila lortuko denaz.)

I’ve already mentioned that having at least some government debt outstanding helps the economy function better. How so?

Right answer- deficit spending adds income and net financial assets to the economy to support sufficient spending to get the output sold.

(Erantzun zuzena- defizit gastuak errenta eta finantza aktibo netoak gehitzen dizkio ekonomiari, nahikoa gastu sostengatzeko, outputa saldua izatearren.)

The answer, according to M.I.T.’s Ricardo Caballero and others, is that the debt of stable, reliable governments provides “safe assets” that help investors manage risks, make transactions easier and avoid a destructive scramble for cash.

Wrong answer. Net govt spending provides in the first instance provides dollars (tax credits) in the form of dollar deposits in reserve accounts at the Federal Reserve Bank. Treasury securities are nothing more than alternative deposits in securities accounts at the Federal Reserve Bank for those dollars. Both are equally ‘safe’.

(Erantzun okerra. Gobernuaren gastu netoak lehendabizikoz dolarrak hornitzen ditu (zerga kredituak) dolar gordailuen forman, Erreserba Federaleko erreserba kontuetan. Altxor Publikoen tituluak Erreserba Federaleko tituluen kontuetan dolar horietako gordailu alternatiboak baino ez dira. Biak daude era berean ‘seguru’.)

Now, in principle the private sector can also create safe assets, such as deposits in banks that are universally perceived as sound. In the years before the 2008 financial crisis Wall Street claimed to have invented whole new classes of safe assets by slicing and dicing cash flows from subprime mortgages and other sources.

But all of that supposedly brilliant financial engineering turned out to be a con job: When the housing bubble burst, all that AAA-rated paper turned into sludge. So investors scurried back into the haven provided by the debt of the United States and a few other major economies. In the process they drove interest rates on that debt way down.

Rates went down in anticipation of future rate setting by the fed.

What investors did was reprice financial assets. Investors can’t change total financial assets. The total only changes with new issues and redemptions/maturities.

(Tasak behera joan ziren Fed-ek etorkizuneko tasa ezartzearen aldez aurretik.

Inbertsiogileek egin zutena finantza aktiboen prezio aldatzea zen. Inbertsiogileek ezin dituzte finantza aktibo totalak aldatu. Totala soilik ldatzen da jaulkipen berriekin eta kitapenekin/epemugekin.)

And those low interest rates, Mr. Kocherlakota declares, are a problem. When interest rates on government debt are very low even when the economy is strong, there’s not much room to cut them when the economy is weak, making it much harder to fight recessions.

True, but cutting rates doesn’t fight recessions. In fact low rates reduce interest income paid by govt to the economy, thereby weakening it.

(Egia da, baina tasa murrizketek ez dituzte atzeraldiei aurre egin. Izan ere, tasa baxuek gobernuak ekonomiari ordaindutako interes errenta murrizten dute, eta beraz, bera ahuldu.)

There may also be consequences for financial stability: Very low returns on safe assets may push investors into too much risk-taking — or for that matter encourage another round of destructive Wall Street hocus-pocus.

That would be evidenced by an increase in the issuance of higher risk securities, but there has been no evidence of that. In fact, it was $100 oil that at the margin drove the credit expansion that supported GDP growth, as evidenced by the collapse when prices fell.

(Hori frogatuko luke arrisku handiagoko tituluetan jaulkipen gehitze batek, baina ez da gertatu horrelako frogarik. Izatez, 100 dolarreko petrolioa izan zen, zeinak marjinatan kreditu hedapena gidatzen duen, BPGren hazkundea sostengatzen zuena, prezioak erori zirenean, gainbeherak frogatu zuen moduan.)

What can be done? Simply raising interest rates, as some financial types keep demanding (with an eye on their own bottom lines), would undermine our still-fragile recovery.

It would more likely very modestly strengthen it from the increase in the govt deficit due to the increased interest income paid by govt to the economy. However, I’d prefer a tax cut and/or spending increase to support GDP, rather than an interest rate increase. But that’s just me…

(Litekeenez oso apalki indartuko luke gobernuaren defizitaren gehitze batek, ekonomiari gobernuak ordaindutako interes errenta gehituak direla eta. Hala ere, zerga mozketa bat edo/eta gastuaren gehikuntza bat nahiago nuke BPG sustengatzeko, interes-tasa gehikuntza baino. Baina hori nire ustea da…)

What we need are policies that would permit higher rates in good times without causing a slump. And one such policy, Mr. Kocherlakota argues, would be targeting a higher level of debt.

Mr. K isn’t wrong, but again I’d rather just have a larger tax cut to get to the same point, but, again, that’s just me…

(K jauna ez dago oker, baina berriro ere nahiago nuke zerga mozketa handiago bat puntu berera iristeko, baina, berriz ere, hori nire iritzia da…)

In other words, the great debt panic that warped the U.S. political scene from 2010 to 2012, and still dominates economic discussion in Britain and the eurozone, was even more wrongheaded than those of us in the anti-austerity camp realized.

True, and this author…

(Egia da, eta egile hau…)

Not only were governments that listened to the fiscal scolds kicking the economy when it was down, prolonging the slump; not only were they slashing public investment at the very moment bond investors were practically pleading with them to spend more; they may have been setting us up for future crises.

True but for differing reasons. It’s never about investors pleading. It’s always about the public purpose behind the policies.

(Egia, baina arrazoi desberdinengatik. Ez da inoiz inbertitzaileen aitzakiaz. Politiken atzean dagoen helburu publikoari buruz da beti.)

And the ironic thing is that these foolish policies, and all the human suffering they created, were sold with appeals to prudence and fiscal responsibility.

The larger problem with this editorial is that the wrong reasons it gives for what’s largely the right policy are out of paradigm reasons that the opposition routinely shoots down and shouts down, easily convincing the electorate that they are correct and the ‘headline left’ is wrong.

Feel free to distribute-

(Editorial honekiko arazorik handiena da hein handi batean politika zuzenaren alde ematen dituen argudio okerrak oposizioak beti ukatzen dituen paradigma argudioetatik kanpo daudela, hautesleria erraz konbentzitzeko haiek zuzen direla eta ‘utzitako titulua’ okerra dela.

Sentitu aske banatzeko. )

Gehigarria:

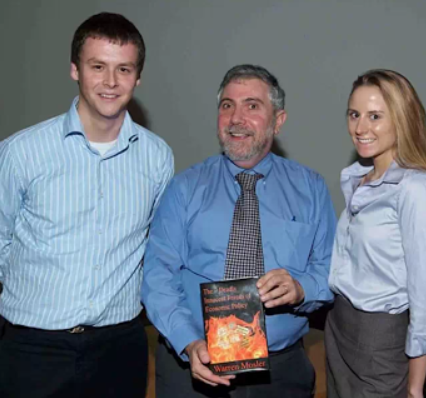

Argazkia: Krugman Mosler-en liburuarekin1

1 Ikus http://moslereconomics.com/2013/12/09/19573/?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=feed&utm_campaign=Feed%3A+TheCenterOfTheUniverse+%28The+Center+of+the+Universe%29.